History – Post 1967

Major developments in national Aboriginal health policy since 1967

Majority of Aboriginal health history information was sourced from The HealthInfoNet website an award-winning resource translating knowledge and academic literature for Aboriginal health workers in Australia. The site was started in 1997.

Visit www.healthinfonet.ecu.edu.au for more information.

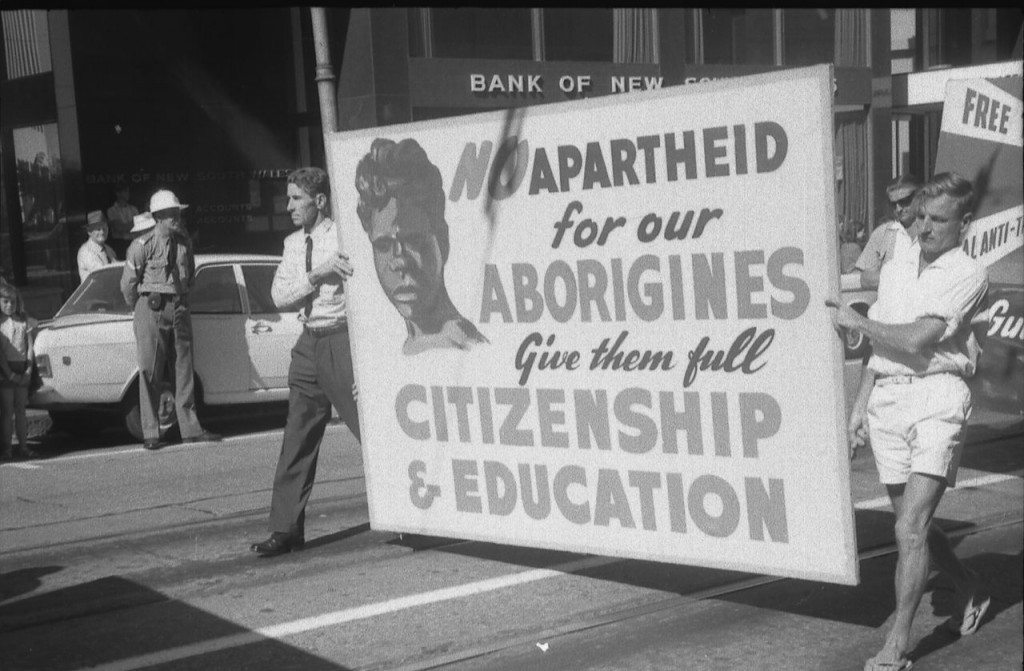

1967

A constitutional amendment referendum held during Liberal Prime Minister Harold Holt’s term in office, gave the Commonwealth Government power to legislate for Indigenous Australians, and allowed for their inclusion in the census [1].i

1968

The Commonwealth Office of Aboriginal Affairs was established [2].

1969

The Office identified health as one of four major areas for Indigenous development and initiated specific purpose grants to the States for the development of special Aboriginal health programs [3] [4] [5]. State government health authorities decided to establish Aboriginal health units to address the health needs of the Indigenous population and to administer the Commonwealth funds [2] [4].

1971

The first Aboriginal Medical Service (AMS) was initiated on a voluntary basis in Redfern, Sydney [6].

1972

The Whitlam Labor Government was elected and replaced the Office of Aboriginal Affairs with the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (DAA) [7]. The DAA continued with the States grants programs initiated by the Office but also began to make direct grants to the newly-emerging AMSs [8].

The Federal Court decision in Australia’s first native title case, the Gove Land Rights Case, found that traditional laws, customs and land rights were not recognised by Australian courts.

1973

The Commonwealth Government made a formal offer to the State Ministers to assume from them full responsibility for Indigenous affairs policy and planning. With the exception of Queensland, all the States accepted the offer and negotiations commenced for the transfer of responsibility for Indigenous policy, planning and coordination from the States to the Commonwealth. The Department of Aboriginal Affairs was given central authority for policy administration[9]. An Aboriginal Health Branch was established in the Commonwealth Department of Health to provide professional advice to the Government [10]. One of its first actions was to propose a Ten Year Plan for Aboriginal Health [7].

1974

The national AMS umbrella organisation, the National Aboriginal and Islander Health Organisation (NAIHO), was formed [11].

1975

The Racial Discrimination Act was introduced, preventing governments from discriminating on the basis of race and ensuring compensation for any removal of Indigenous rights. The universal health insurance system, Medibank, was introduced making mainstream health services more affordable [11].The Liberal-National Country Coalition Government, led by Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, was elected.

1976

The Report on the Delivery of Services by the Department of Aboriginal Affairs was published. It assessed the capability of the DAA to fulfil its responsibilities for Indigenous policy development and administration [9].

The Commonwealth-funded National Trachoma and Eye Health Program was launched [12].

The Commonwealth asked the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs (HRSCAA) to conduct a review of Aboriginal health [7].

1977

The HRSCAA inquiry was initiated [13].

The Australian Parliamentary report Alcohol problems of Aboriginals was published [14].

1978

The Commonwealth Coalition Government terminated Medibank, the universal health insurance scheme [11].

1979

The HRSCAA’s report Aboriginal Health was released [15].

1980

The Royal Australian College of Ophthalmologists produced The National Trachoma and Eye Health Program report [12].

The Aboriginal Development Commission was established. One of its primary functions was to provide advice to the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs on matters pertaining to Indigenous social and economic development [9].

An internal Commonwealth Government report, the Program Effectiveness Review, was never officially released to the public but considered, among other things, the issue of Indigenous involvement in Indigenous health policy development, the introduction of specific Indigenous health initiatives and the existing arrangements for funding and administration of Indigenous health [1].ii

1981

The Commonwealth Government initiated a $50 million five-year Aboriginal Public Health Improvement Program in response to recommendations outlined in the HRSCAA report [7]. The program, administered by the DAA, focused on unsatisfactory environmental conditions associated with inadequate water, sewerage and power systems [3].

1983

Labor Prime Minister Bob Hawke was elected.

1984

Responsibility for all Commonwealth Aboriginal health programs, including the Department of Health’s role in the funding of some AMSs, was consolidated within the Department of Aboriginal Affairs [4].iii

Universal health insurance was reintroduced as Medicare [11].

A Commonwealth Task Force on Aboriginal Health Statistics was established [16].

1985

The Canberra-based Australian Institute of Health (AIH) was established within the Commonwealth Department of Health. It was given Commonwealth responsibility for the development of Indigenous health statistics [17].

1987

The Commonwealth Departments of Health and Community Services merged to form the Department of Community Services and Health.

The Australian Institute of Health (AIH) became an independent statistics and research agency. It continued to play an important role in the development of Indigenous health statistics [17].

A meeting of Commonwealth, State and Territory Health and Aboriginal Affairs Ministers led to the formation of a Joint Ministerial Forum on Indigenous health and the appointment of a National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party (NAHSWP). The NAHSWP was to develop a strategy on Indigenous health that would encompass issues pertaining to funding, Indigenous participation, intersectoral coordination and monitoring and meet with the approval of all stakeholders [1] [7].

1988

The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody was initiated [18].

1989

The National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party (NAHSWP) final report, A National Aboriginal Health Strategy (NAHS) [19], was presented to the Joint Ministerial Forum [1].

The Ministerial Forum established the Aboriginal Health Development Group (AHDG), comprised primarily of Commonwealth, State and Territory government representatives, to assess the report and advise on its implementation [1] [7].

AMSs protested against the limited representation of Indigenous community interests on the AHDG and a community advisory group, the Aboriginal Health Advisory Group (AHAG), was subsequently established in parallel to the AHDG [1][7].

The third national health survey (conducted by the ABS) provided, for the first time, for the identification of Indigenous people[20].

1990

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was established, replacing the DAA and the Aboriginal Development Commission, and assumed national responsibility for Indigenous health.

The AHDG’s Report to Commonwealth, State and Territory Ministers for Aboriginal Affairs and Health was released[7].

AHDG recommendations, including the need for: a Council for Aboriginal Health; State/Territory Tripartite Forums; a specialised health branch, the Office of Aboriginal Health, within ATSIC; and a national Aboriginal community-controlled health organisation, were accepted by the Joint Ministerial Forum [21]. Commonwealth Ministers within the Joint Ministerial Forum submitted the NAHS to Cabinet for a formal Commonwealth response[1].

In addition to a number of pre-existing Commonwealth-funded programs perceived to fall under the NAHS umbrella, the Commonwealth Government allocated $232.2 million (over five years) for implementation of aspects of the Strategy. Of the $232.2 million, $171 was allocated for housing and infrastructure, $47 for health services, $6.3 for ATSIC running costs, $7.3 for the National Campaign Against Drug Abuse (NCADA) projects targeting Indigenous people and $0.6 for the Australian Institute of Health [22] [23]. The total allocation was far less than the $3 billion estimated as necessary for full implementation of the NAHS.iv

1991

The Commonwealth Department of Community Services and Health was restructured and renamed the Department of Health, Housing and Community Services.

The extension of the Australian Institute of Health’s focus to include the areas of disabilities and children’s services was accompanied by a change in name to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW).

ATSIC produced an interim report Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Goals and Targets [24], which was proposed as a means of evaluating the effectiveness of the NAHS [6] [7].

The final report of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCADC) [18] was published. The report comprehensively reviewed Indigenous health needs, government strategies addressing those needs, and the efficacy of existing programs [7]. Its recommendations asserted explicit support for the implementation of the NAHS [1].

The NHMRC’s Guidelines on Ethical Matters in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Research [25] were endorsed.

Labor was returned to power under the leadership of Prime Minister Paul Keating.

1992

The High Court judgement in the Mabo Case, Australia’s second native title case, overturned the colonial concept of terra nullius (that Australia was not recognised as belonging to anyone prior to its occupation by the British). The Federal Court’s Gove decision was overruled and the High Court held that courts do recognise traditional Indigenous land and water rights [26].

A number of outstanding issues in the implementation of the NAHS reached a degree of resolution. Negotiations with State and Territory governments regarding matching financial commitments ceased and Commonwealth funds were distributed through ATSIC regional councils to community controlled organisations [1]. The Council for Aboriginal Health (CAH), intended to advise governments on Indigenous health policy and monitor the performance of the NAHS, met for the first time [7].

The Commonwealth Government announced a $150 million five-year funding package, principally for the establishment of Aboriginal-controlled drug and alcohol services [7].

ATSIC and the Australian Construction Services commenced a two-stage survey of Indigenous housing and community infrastructure needs [27].

The National Commitment to Improved Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People was endorsed, providing a framework for bilateral agreements between the Commonwealth and State/Territory governments to improve programs and services for Indigenous people [28].

1993

Commonwealth department restructuring resulted in the formation of the Department of Health, Housing, Local Government and Community Services.

The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) was established as the new national AMS umbrella organisation, replacing NAIHO which had ceased operation some 5 years earlier.

The Commonwealth Ministers for Health and Aboriginal Affairs initiated a review of the Council for Aboriginal Health [21].

Public calls were made for responsibility for Indigenous health to be moved from ATSIC to the Commonwealth health department [7].

The Wik peoples made a native title claim in the Federal Court [29].

The Native Title Act became law [29]. The Act was intended to recognise and protect native title, and give Indigenous land rights, as stated in the Mabo Case, statutory authority.

1994

The Commonwealth Government announced a $500 million five-year health package, the majority of which involved a continuation of existing NAHS activities [7].

ATSIC established the Health Infrastructure Priority Projects (HIPP) scheme. The Scheme addressed environmental health issues through large-scale construction of housing and infrastructure [7].

A high-level Evaluation Committee appointed by the Commonwealth Ministers for Health and Aboriginal Affairs noted that the National Aboriginal Health Strategy had never been effectively implemented and that all governments had grossly under-funded initiatives in remote and rural areas [23].

The Australian Bureau of Statistics conducted the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey [30].

The NHMRC established a Research Strategy and Development Committee, which in turn set up a Working Party on Indigenous health research [23].

A Joint Health Planning Committee, comprising Commonwealth health department, ATSIC and NACCHO representatives, was established to approve funding allocations for Indigenous health projects [4].

In 1994-95, Commonwealth funding of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health and substance abuse services amounted to $85.4 million [4].

1995

Responsibility for Indigenous health was transferred from ATSIC to the Commonwealth health department – renamed the Department of Human Services and Health (DHSH) the year before – and the Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Services (OATSIHS) was established [31].

Following the 1992 National Commitment to Improved Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, Health Ministers agreed to a process for the development of multilateral framework agreements with States and Territories [4]. The Framework Agreements provided for the establishment of consultative national and State/Territory forums to provide policy and planning advice on Indigenous health issues [32].

The DHSH and ATSIC instituted a Memorandum of Understanding defining their roles and responsibilities [31].

The Australian Bureau of Statistics conducted a National Health Survey including an enhanced sample of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians providing national estimates on Indigenous health status.

In the 1995-96 financial year, the Commonwealth funded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health and substance abuse services (including transfers from other programs) to the sum of $120.7 million [4].

1996

The Federal Court decided against the Wik peoples 1993 land claim on the basis that their native title rights had been extinguished by existing pastoral leases [29].

Following thirteen years of Labor rule, a Liberal-National Coalition Government, led by Liberal Prime Minister John Howard, was elected. The Department of Human Services and Health was renamed the Department of Health and Family Services (DHFS) [4].

The Commonwealth Minister for Health announced the establishment of the national health advisory forum proposed in the Framework Agreements, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council [33].

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Welfare Information Unit (ATSIHWIU) – a joint program of the AIHW and the ABS – undertook a review to develop a National Plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Information [34].

Commonwealth approval was extended for all existing AMSs to bulk-bill Medicare [4].

The Commonwealth Minister for Health launched the $20 million National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Emotional and Social Well Being (Mental Health) Action Plan [32].

The Commonwealth Minister for Health approved implementation of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Hearing Strategy [32].

By the end of the year, six of the eight States and Territories had signed the Framework Agreements, agreed to by all Health Ministers in 1995 [4].

The High Court overturned the Federal Court’s Wik decision. It was held that native title was not necessarily extinguished by pastoral leases, and that both native title and pastoral rights could exist over the same land [26] [35].

In the 1996-97 financial year, Commonwealth allocations to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health and substance abuse services (including transfers from other programs) totalled $121.8 million [4].

1997

In response to the Wik decision, the Commonwealth Government presented to parliament the Native Title Amendment Bill 1997. The Bill proposed changes to the Native Title Act based on amendments made in 1996 and those derived from the Coalition’s Ten Point Plan [26].

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs initiated an Inquiry into Indigenous Health in response to a joint request from the Commonwealth Ministers responsible for health and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander affairs.

The NHMRC published the report Promoting the Health of Indigenous Australians: A review of infrastructure support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health advancement [33].

Development of the National Indigenous Australians’ Sexual Health Strategy (1996/97 to 1998/99) was finalised and launched [36].

The national review Eye Health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities [37] was presented to the Minister [36].

A set of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Indicators and Targets were endorsed by all Health Ministers [36].

The ABS and the AIHW launched the report The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples [38] which provided up-to-date statistics about Indigenous health and welfare.

Health Ministers agreed to The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Information Plan for improving the quality of Indigenous health data [32].

The Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission released Bringing them home: report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families [39].

A Joint NACCHO/Departmental Working Group was established to review current arrangements for Indigenous access to Commonwealth health program funding [4].

Two new NHMRC sub-committees, the Research Agenda Working Group and the Strategic Health Research Working Group, were established to guide and oversee Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research [32].

The National Training and Employment Strategy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Professionals Working in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health was released [32].

Discussions occurred between State/Territory health departments and NACCHO affiliates regarding plans for the development of a National Indigenous Australians’ Health Strategy [32].

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs released the first of a series of volumes containing submissions received in response to their Inquiry into Indigenous Health [40].

The Health Insurance Commission review Market research into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander access to Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme was published [41].

In the 1997-98 financial year, the Commonwealth allocated $135.8 million (including transfers from other programs) to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health and substance abuse services [4].

1998

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare released the review Expenditures on health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people [42].

The Health Infrastructure and Capital Replacement Program was developed to provide a strategic approach to the maintenance and upgrading of health infrastructure and the provision of accommodation for health personnel in Indigenous communities [43].

The first annual Service Activity Reporting (SAR) questionnaire was sent to all Commonwealth-funded Aboriginal primary health care services. The SAR is a joint initiative of NACCHO and OATSIH and collects data on the key activities of the services.

The Department of Health and Family Services was restructured, following John Howard’s re-election as Prime Minister, and renamed the Department of Health and Aged Care to reflect its changed responsibilities and functions [4].

The Australian National Audit Office concluded its performance audit of the Department of Health and Aged Care and released its report Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program [4].

The final two jurisdictions, Tasmania and the Northern Territory, signed Framework Agreements [4].

An estimate of Commonwealth funding for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health and substance abuse services over the 1998-99 financial year amounted to $158.4 million (including transfers from other programs) [4].

1999

The Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Services (OATSIHS) was renamed the Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (OATSIH) to reflect more accurately its long term strategy and work. OATSIH continues to operate within the Commonwealth department responsible for health.

The Australian National Audit Office concluded its performance audit of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission and released its report National Aboriginal Health Strategy – delivery of housing and infrastructure to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities [44].

The Primary Health Care Access Program (PHCAP) was announced in the 1999-2000 Commonwealth Budget. The Program is aimed at improving access to primary health care by facilitating increased community-control, reforming existing health systemstructures, and increasing the available resources within selected sites.

The Commonwealth Minister for Health and Aged Care restructured the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council.

2000

The House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs tabled its final report Health is life [45]. The report documents the Committee’s recommendations following the inquiry into the health status of Indigenous Australians.

Data on the activities of Commonwealth-funded, stand-alone Indigenous substance use services was collected for the 1999-2000 period. The data provides the first national statistics pertaining to the work of these services.

2001

In February, the Australian Health Minister’s Advisory Council (AHMAC) agreed to the development of an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce National Strategic Framework. The Framework objectives were endorsed by AHMAC in October. AHMAC also agreed to a consultation process for key stakeholders and the development of an implementation plan.

The Northern Territory and South Australia re-signed Framework Agreements.

Redfern Aboriginal Medical Service celebrated 30 years of health care provision to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council released for discussion the draft National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Strategy [46].

The Commonwealth Government tabled its response to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs report Health is Life [47].

The Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care released The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander coordinated care trials national evaluation report: volume 1 – main report [48]. It outlines the background, descriptions, experiences and outcomes of the four coordinated care trials conducted in Aboriginal communities between 1997 and 1999. The trials took place in Katherine (NT), the Tiwi Islands (NT), Wilcannia (NSW) and Perth/Bunbury (WA).

The report Better health care: studies in the successful delivery of primary health care services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians [49] was published by the Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care. The publication examines the concept of comprehensive primary health care, provides national and international evidence of the effectiveness of this approach in improving health outcomes of Indigenous people, and illustrates the success of this approach through a series of case studies on successful health service interventions.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare released the report Expenditures on health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 1998-1999 [50]. The report provides information on the health expenditure for Indigenous Australians across the nation.

AHMAC agreed to establish the Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (SCATSIH). SCATSIH supersedes the Heads of Aboriginal Health Units (HAHU) forum.

The Department of Health and Aged Care was renamed the Department of Health and Ageing.

2002

In April, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to commission the Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth/State Service Provision (SCRCSSP) to produce a regular report to COAG against key indicators of Indigenous disadvantage. The purpose of the reports is to measure the impact of policy changes on the Indigenous community.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce National Strategic Framework was released for endorsement by AHMAC [51].

Victoria and Western Australia re-signed their respective Framework Agreements.

Following a consultative process, the NHMRC Road Map: a strategic framework for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health through research[52]. The purpose of the consultation was to identify areas of research that would underpin better policy and practice to improve Indigenous health.

The Australian National Audit Office concluded its follow-up to the 1998 performance audit of the Department of Health and Ageing. The ANAO reviewed the extent that the Department had implemented recommendations [53].

The AIHW released the report Australia’s Health 2002. The report included detail on the state of Indigenous health [54].

In October, OATSIH and the Office of Hearing Services published their report on Commonwealth funded hearing services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: strategies for future action. The report outlined a set of policy principles and strategies to guide future action in addressing the continued prevalence of Otitis Media and hearing loss in Indigenous people [55].

2003

The ABS and the AIHW published the 4th edition of the biennial report The health and welfare of Australia’s Indigenous Peoples 2003 [56].

The Australian and State/Territory governments endorsed the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: framework for action by governments. All Health Ministers signed the framework in July. The National Strategic Framework is a complementary document that builds on the 1989 National Aboriginal Health Strategy and addresses approaches to primary health care within contemporary policy environments [57].

The Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health began development of a national Indigenous Maternal and Child Health policy framework.

ATSIC released the Family Violence Action Plan. The Action Plan outlines policy addressing family violence in communities and has a direct focus on improving the health and social environment of individuals and communities.

The SCRCSSP released the report Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2003. The report is a formally endorsed framework by COAG [58].

The Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing published a consultation paper for The development of a national strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2004-2009. The consultation was presented to a diverse audience for consideration, with the hope that the recommended actions in the paper would provide the basis for Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing over the next 5 years [59].

2004

In early 2004, the Australian Government announced the introduction of significant changes to the way policies, programs and services were developed and delivered to Indigenous people and communities. Responsibility for the delivery of all Indigenous-specific programs was transferred to mainstream agencies and a’whole-of-government’ approach adopted. This new approach was based on a process of negotiating agreements with Indigenous families and communities at the local level in accordance with the concepts of mutual obligation and reciprocity for service delivery.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) and its service delivery arm, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS), were subsequently abolished. To coordinate the approach at the national level, an Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination was established within the Department of Immigration, Multicultural and Indigenous Affairs. For an overview of key developments see the summary provided in the Social justice report 2004.

In January, the Australian Government committed $7 million in research grants with the goal of improving the health of Indigenous people. The research grants, made available through the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), aimed to increase the understanding of lifestyle, culture, and environment, in order to develop more effective health programs.

In May, the Australian Government released the Review of the implementation of the national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander eye health program. The review concluded that the program had helped to provide eyecare services Indigenous people, particularly those in rural and remote areas.

The Australian Government introduced a new health check for Indigenous Australians covered by Medicare in May. The two yearly checks aimed to ensure early diagnosis and intervention for treatable conditions for Indigenous Australians aged 15-59.

In June, COAG agreed to the National framework of principles for government service delivery to Indigenous Australians which provided a common framework between governments promoting flexibility and tailored responses to form partnerships with Indigenous communities. At the same meeting in June, COAG also agreed to the National framework on Indigenous family violence and child protection that aimed to improve engagement and cooperation between governmental jurisdictions and Indigenous communities to help tackle these issues.

In June, ABS released its second survey of Indigenous Australians, The national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social survey, 2002. This report documented the improvements in employment and education of Indigenous people, but outlined the continuing disadvantages experienced by Indigenous populations in these two areas, noting that particularly in health there had been little progress.

1 July 2004, the new governmental changes regarding the “whole-of-government” approach to Indigenous affairs at a Federal level began being implemented.

The Australian Medial Association (AMA) released the Indigenous health workforce needs report in July, outlining the need to expand the Indigenous health workforce and improve the provision of health services to Indigenous people.

2005

The second UN supported International Decade of the World’s Indigenous People, aimed at strengthening international cooperation in difficulties faced by Indigenous people in the arenas of culture, education, health, human rights, the environment, and development, commenced on 1 January.

The Federal Government declared in January that it would double the Indigenous Family Violence Prevention Legal Services Program, increasing its services nationwide from 13 to 26 sites at a cost of $22.7 million over four years.

The Commonwealth Government announced the 2005-06 Budget in May, outlining the Healthy for life initiative. This initiative provided $102.4 million over four years, aiming to improve the health of mothers and children, and better the lives of people with chronic illness.

The Australian Government announced a new Medicare-funded annual health check for Indigenous children in June. The check covered children up to 15 years of age and helped doctors targeted risk factors for chronic illness, such as diabetes and heart disease, substance use, and other health factors that can begin during childhood and adolescence. The check was part of the government’s Healthy for life initiative.

ATSIC Regional Councils were officially disbanded in late June as part of the Government’s restructuring announced in 2004.

In July, AIHW released Expenditures on health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2001-02, the third in a series of reports released every three years. The report outlined and compared governmental and non-governmental funding for Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in 2001-02, and detailed changes that had occurred since 1995 [60].

In the same month, the Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth Service Provision published their second report detailing Indigenous disadvantage in seven strategic areas, Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2005: report [61].

The ABS and AIHW published Health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2005 in August. This major report detailed the health of Indigenous people and compared it with the health of non-Indigenous people [62].

The framework, Social and emotional well being framework: a national strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and social and emotional wellbeing 2004-09, was published in October. This framework provided a five year plan to guide organizations in their work regarding social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous people [63].

The Commonwealth Government published the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Sexual Health and Blood Borne Virus Strategy 2005-2008 in October. This report outlines four key areas for improvement in the prevention of HIV, STIs, and other blood borne infections [64].

In December, the Australian Government announced funding for 27 Indigenous primary health care services. These services received up to $400 000 per year for four years as part of the Healthy for life program. Funding targeted staff increases in child and maternal health, and chronic disease services, as well as health promotion, and education and care plans.

2006

The Social Justice Report 2005 was released by HREOC in February. This report examined the implementation of the new whole-of-government approach Indigenous administration, noting that some developments had emerged but there were some under-addressed gaps in policy, coordination, and representation [65].

In April the ABS released the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health survey: Australia, 2004-05. This report provided a summary of health status, health actions, and lifestyle factors for Australia’s Indigenous people [66].

1 May saw the new implementation Medicare-funded health checks for Indigenous Australians and refugees. The new items included recognition of the role of specialists in pain and palliative care, immunisation and wound management in NT, and child health checks for early detection of treatable conditions.

The National Indigenous Violence and Child Abuse Intelligence Task Force was established in July, led by the Australian Crime Commission (ACC). This task force was designed to address child abuse and violence in Indigenous communities in line with the whole-of-government approach.

In the same month, the Australian Government’s Department of Health and Ageing released the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2003-2013: Australian Government implementation plan 2003-2008, its response to the recommendations made in the National Strategic Framework regarding how the government planned to improve Indigenous health [67].

In July, the Commonwealth Government increased funding to a further 26 sites as part of the Healthy for life program, announced in the 2005-06 budget. These sites will emphasise primary health care services targeting circulatory disease, eye problems, asthma, and diabetes in remote Indigenous communities.

COAG met in mid-July and discussed many Indigenous issues, agreeing to establish a working group to develop a detailed plan for practical reform reflecting the diversity of circumstances in Indigenous communities across Australia. At the same meeting COAG pledged $130 million over four years to support national and bilateral actions addressing violence and child abuse in Indigenous communities. They declared that no customary law or justification of cultural practices excused or lessened the seriousness of violence or sexual abuse. COAG also agreed to provide more funding for drug and alcohol treatment and rehabilitation, and agreed to an early intervention aimed and health checks at improving the health and wellbeing of Indigenous children in remote communities.

In August, the NT Government established a Board of Inquiry to research and report on allegations of sexual abuse among Indigenous children. The Board also aimed to make recommendations for the protection of Indigenous children from sexual abuse.

2007

In April, Oxfam released its report, Close the gap: solutions to the Indigenous health crisis facing Australia, that outlined the disparities of life expectancies between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in Australia, and also compared health of Indigenous people in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States of America. The Close The Gap campaign, comprised 40 of Australia’s leading Indigenous and non-Indigenous health organisations, was launched on 4 April. The campaign aimed for the Federal, State, and Territory Governments to commit to closing the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians within a generation [68].

The NT’s Board of Inquiry, tasked with examining allegations of sexual abuse among Indigenous children, published their report, Ampe akelyernemane meke mekarle: little children are sacred, in April. The report detailed 97 recommendations on a variety of topics, including education and schooling, reducing alcohol consumption, improving family and support services, enhancing cooperation between services and communities, and empowering communities [69].

The outcomes of an evaluation of four programs aimed at improving social and emotional wellbeing of Indigenous Australian were published in May. The examination of Bringing Them Home Counsellors, Link Up Services, and two other programs found that they were culturally appropriate and served a large number of Indigenous people, and should be used as a guide for future programs.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework report 2006 was published in June by AHMAC. The aim was to increase debate and policy innovation as well as informing the analysis, planning, and implementation of policy [70].

Parliament tabled HREOC’s annual Social Justice Report 2006 in June. The report identified two major problems with how the government dealt with Indigenous reform: first, the new whole-of-government approach did not adequately include Indigenous people in decision-making; second, the government had no framework or benchmarks to gauge improved access to services [71].

The Commonwealth Government tightened its restrictions on the importation of kava in late June, to help battle abuse. Importation of kava has been limited to medical or scientific purposes, or to adults of Pacific Islander decent in recognition that kava has traditional ceremonial and cultural significance.

In June, the Nganampa Health Council released preliminary results of a survey indicating that Opal fuel has helped to reduce petrol sniffing among Indigenous communities. The Government has pledged $42.7 million over five years to support the conversion to Opal fuel.

The UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in September, reaffirming the entitlements of international human rights for Indigenous people without discrimination. The Declaration was opposed by Australia and three other nations.

The Australian Government’s Department of Health and Ageing released in October the National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health 2003-2013: Australian Government implementation plan 2007-2013, its second response to the recommendations made in the National Strategic Framework regarding how the government planned to improve Indigenous health [72].

The new Labour government, headed by the Hon. Kevin Rudd MP, was sworn in 3 December.

At COAG’s December meeting, the members committed to closing the difference in life expectancy within a generation, and reducing the mortality gap of children under five, as well as the gap in reading, writing, and numeracy, by half within a decade. Specifically, the Commonwealth Government agreed to double the funding of $49.3 million previously pledged by COAG for services dealing with substance and drug rehabilitation and treatment.

2008

On 13 February, Prime Minister Kevin Rudd formally apologised to members of the Stole Generation on behalf of the government.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Tom Calma, formally responded to the Apology on behalf of the Stolen Generation peak bodies. See

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FxHw1KK_gNw”

A Statement of Intent was signed in March between the Government and Indigenous health leaders, signalling the intent to work together to achieve equality in life expectancy and health status between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians by 2030.

The Social Justice Report 2007 was released in late March by HREOC, outlining a 10 point plan to modify the NT intervention legislation to better protect Indigenous children and families [73].

The Budget was released in May, outlining measures aimed at closing the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. These measures included extra funding for services dealing with maternal and child health, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Indigenous children, substance use, and appropriate health services. Much of the extra funding was directed towards NT.

In July the report entitled Progress of the Northern Territory emergency response child health check initiative: health conditions and referrals was released. It provided information on the number and types of health conditions and referrals made as part of the child health checks from July 2007 to May 2008 [74].

Nicola Roxon, Minister for Health and Ageing, announced the composition of the Indigenous Health Equality Council on 10 July 2008.The Council, to be chaired by Professor Ian Anderson, will advise on the development and monitoring of health-related goals to support the Government’s commitment to closing the gaps in health between Indigenous and other Australians.

The Close the Gap coalition presented the Federal Government and Opposition with a set of National Indigenous Health Equality Targets in July. The targets aim to address the 17-year gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Nicola Roxon, Minister for Health and Ageing, outlined in September the Rudd Government’s plans to ‘close the gap’ in health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The Northern Territory Emergency Response Review Board’s report, released in October, provides an independent assessment of the progress of the Emergency Response.

The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) announced in November a commitment of $4.6 billion for Indigenous issues. The funds will focus on projects across the areas of early childhood development, health, housing, economic development and remote service delivery.

The Australian Medical Association’s 2008 report card, Ending the cycle of vulnerability: the health of Indigenous children – released in November – outlines the significant gaps in health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children.

2009

Closing the gap on Indigenous disadvantage: the challenge for Australia, which summarises the Australian Government’s progress in ‘closing the gap’ and addressing Indigenous disadvantage was released in January.

In January, the Department of Health and Ageing released Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework report 2008, which highlights vital aspects of Indigenous health.

Jenny Macklin, Indigenous Affairs Minister, announced in April Australia’s official support of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which had been adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007.

The Social Justice 2008 report, released in May, focuses on: human rights protection for Indigenous peoples; remote Indigenous education; Indigenous healing; and the progress on achieving Indigenous health equality.

Federal Treasurer Wayne Swan delivered in May his second Budget, which allocates an additional $1.3 billion for Indigenous health. The funding includes: $131million over three years for Indigenous health services in the NT, $58 million over four years for ear and eye services, $11 million for oral health in rural and regional areas, and $13.8 million for link-up services.

ABS released in May revised estimates of the life expectancy of Indigenous people in Australia. The new estimates suggest a life expectancy gap of about 10 years, down from previous estimates of an almost 17 year gap.

The Australian Government announced in June the appointment of Warren Snowdon, the former Defence Science and Personnel Minister, as Minister for Indigenous Health, Rural and Regional Health and Regional Services Delivery.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Tom Calma, provided a report in August outlining a proposed new structure for a National Indigenous Representative Body to replace ATSIC. The report recommends that the body should be independent of government and have equal gender representation.

Justin Mohamed was elected as the new Chair of NACCHO (National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation in November.

The Australian Government announced in November the establishment of the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples, the new national representative body for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Mr Mick Gooda, a descendent of the Gangulu people of central Queensland and former CEO of the Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health, was named in December new Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner.

2010

January: The Social justice report 2009, the final report by Tom Calma as Social Justice Commissioner was released, the focus of the report was justice reinvestment to reduce Indigenous overrepresentation in the criminal justice system, protection of language and sustaining Aboriginal homeland communities [75].

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers Association was launched by Warren Snowdon, Minister for Indigenous health, $1.2m in funds will be provided over a three year period to investigate national registration and accreditation strategies [76].

February: Tom Calma was appointed as the inaugural National Coordinator for tackling Indigenous smoking; $100.6m has been allocated through this measure under COAG’s NPACTG in Indigenous health outcomes [77].

Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, released his second Closing the gap statement to Parliament which outlined baseline measures against which progress will be compared in the longer term [78].

The Close the Gap Steering Committee for Indigenous Health Equity released an inaugural Shadow report on the Australian Government’s progress towards closing the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. This report called for increased Indigenous participation in policy-making processes and a national plan for achieving Indigenous health equality within a generation [79].

March: NIEHC released two reports; the Child mortality targets: recommendations and analysis which gives direction and context on the progress of the COAG’s aim to halve the gap in Indigenous children under five mortality rates within a decade (progress being made) and the second report; National target setting instrument; evidence based best practice guide, a best practice guide for policy makers [80], [81].

April: The SCRGSP released the Report on government services: Indigenous compendium (2010) which focused on early childhood, education and training, justice, emergency management, health, community services and housing [82].

The National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples was established as an incorporated body, succeeding ATSIC as an advocate for the recognition of Indigenous peoples’ rights [83].

May: The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s health strategy, to address the gap in women’s health between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was released [84].

Federal Treasurer Wayne Swan delivered his third Australian Government budget, building on its commitment to close the gap in life expectancy and opportunities for Indigenous Australians, through working partnerships, focusing on community safety, employment, education and early childhood, housing flexible remote service delivery, Indigenous broadcasting and Indigenous legal assistance services [85].

Australia’s first national male health policy, including $6m over three years to promote the role of Indigenous fathers and partners, grandfathers and uncles, to engage them in their children’s lives, especially early childhood and antenatal periods was launched [86].

June: The Third national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander blood borne viruses and sexually transmissible infections strategy focusing on testing, treatment and follow-up; primary prevention activities; young people; and workforce development initiatives was launched [87].

Under legislation passed by the Commonwealth Parliament in June 2010, all of the provisions in the Northern Territory Emergency Response legislation that suspended the operation of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 were removed. Many measures under NTER had been redesigned to make them consistent with the Act, where necessary, while legislative provisions which deemed certain initiatives, such as income management and alcohol and pornography restrictions, to be special measures, were repealed [88].

July: The Indigenous Allied Health Australia Incorporated national body to represent Aboriginal and Torres Strait allied health professional and students was launched [89].

September: Ken Wyatt, the first Indigenous Australian member of Parliament’s lower house was honoured in a traditional ceremony. The ceremony was an important recognition of Indigenous Australian traditions and a significant event in Australian history [90].

November: The Prime Minister Julia Gillard announced that the Federal Government would establish an independent panel of experts to provide advice on the best way to recognise Indigenous Australians in the constitution. The expert panel would include Indigenous and community leaders, constitutional experts, and parliamentary members [91].

December: Warren Snowdon, Minister for Indigenous Health launched the national Tackling smoking and healthy workforce, funding was provided for 82 positions aimed at reducing smoking and improving nutrition and physical activity in Indigenous communities [92].

References

- Anderson I (1997) The National Aboriginal Health Strategy. In: Gardner H, ed. Health policy in Australia. Melbourne: Oxford University Press: 119-135

- Franklin M, White I (1991) The history and politics of Aboriginal health. In: Reid J, Trompf P, eds. The health of Aboriginal Australia. Marrickville: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group [Australia] Pty Ltd: 1-36

- Thomson N (1984) Australian Aboriginal health and health-care. Social Science & Medicine; 18(11): 939-48

- Australian National Audit Office (1998) The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Program: Department of Health and Aged Care. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office

- Altman J, Sanders W (1991) From exclusion to dependence: Aborigines and the welfare state in Australia. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research, Australian National University

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1993) Annual Report 1992-93. Woden: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

- Gardiner-Garden J (1994) Innovation without change? Commonwealth involvement in Aboriginal health policy. Canberra: Parliamentary Research Service

- Anderson I, Sanders W (1996) Aboriginal health and institutional reform within Australian federalism. Canberra: Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research

- Osborne P (1982) The other Australia: the crisis in Aboriginal health. Hobart: University of Tasmania

- Thomson N (1985) Aboriginal health: status, programs and prospects. : South Australian Health Commission

- Saggers S, Gray D (1991) Aboriginal health and society: the traditional and contemporary Aboriginal struggle for better health. North Sydney: Allen and Unwin

- Royal Australian College of Ophthalmologists (1980) The national trachoma and eye health program of the Royal Australian College of Ophthalmologists. Sydney: Royal Australian College of Opthalmologists

- Thomson N (1987) Towards a National Aboriginal health policy [draft]. : Australian Institute of Health

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs (1977) Alcohol problems of Aboriginals: final report. Canberra: House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs, Ruddock PM (1979) Aboriginal Health: report from the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal Affairs. Canberra: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia

- Thomson N (1986) Recent developments in Aboriginal health statistics. Paper presented at the Proceedings from the Aboriginal Health Statistics workshop. , Darwin

- Australian Institute of Health (1988) Australia’s health 1988: the first biennial report of the Australian Institute of Health. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health

- Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1991) Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody: National reports [Vol 1-5], and regional reports. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party (1989) A national Aboriginal health strategy. Canberra: Department of Aboriginal Affairs

- Thomson N (1991) A review of Aboriginal health status. In: Reid J, Trompf P, eds. The health of Aboriginal Australia. Marrickville, NSW: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Group [Australia] Pty Ltd: 37-39

- Codd M (1993) Developing a partnership: a review of the Council for Aboriginal Health. : Council for Aboriginal Health Review Team

- Thomson N, English B (1992) Development of the National Aboriginal Health Strategy. Aboriginal Health Information Bulletin; 17: 22-30

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Evaluation Committee (1994) The National Aboriginal Health Strategy: an evaluation. Canberra: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

- Wronski I, Smallwood G (1992) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health goals and targets [interim]. Canberra: National Better Health Program; Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission.

- National Health and Medical Research Council (1991) Guidelines on ethical matters in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health research. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1997) Native title amendment bill 1997: issues for indigenous peoples. Canberra:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, Australian Construction Services (1993) 1992 National Housing and Community Infrastructure Needs Survey. Canberra: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission

- Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation and Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (1998) Towards a benchmarking framework for service delivery to Indigenous Australians: proceedings of the Benchmarking Workshop 18-19 November 1997. Canberra: Council for Aboriginal Reconciliation

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1997) A plain English guide to the Wik case. Canberra:

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (1995) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Survey 1994. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service

- Richardson S (1997) The politics of Aboriginal health in Australia – since the Working Party. Challenging Public Health; 1: 58-69

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services (1997) Submission from the Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs Inquiry into Indigenous Health. In: Inquiry into Indigenous health, submissions authorised for publication, national organisations. Canberra: House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs: 215-316

- National Health and Medical Research Council (1996) Promoting the health of Indigenous Australians: a review of infrastructure support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health advancement. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Welfare Information Unit (1997) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health information: quality data through national commitment: final report to Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council. Darwin: Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (1997) The ten point plan on Wik and native title : issues for Indigenous peoples. Canberra:

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services (1997) Program 3: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. In: Annual Report 1996-97. : Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services.:

- Taylor HR (1997) Eye health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (1997) The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: A joint program of the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families (1997) Bringing them home: report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. Retrieved 17 November 2011 from http://www.humanrights.gov.au/pdf/social_justice/bringing_them_home_report.pdf

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs (1997) Inquiry into Indigenous health, submissions authorised for publication, national organisations. Canberra:

- Keys Young (1997) Market research into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander access to Medicare and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme [report]. Canberra: Prepared for Health Insurance Commission

- Deeble J, Mathers C, Smith L, Goss J, Webb R, Smith V (1998) Expenditures on health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: final report. Canberra: National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services (1998) Budget 1998-99: summary of initiatives in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health [on-line]. : Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services.

- Australian National Audit Office (1999) National Aboriginal Health Strategy: delivery of housing and infrastructure to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs (2000) Health is life: report on the inquiry into Indigenous health. Canberra: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council (2001) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Strategy: draft for discussion. Canberra: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council

- House of Representatives Standing Committee on Family and Community Affairs (2001) Government response to the House of Representatives Inquiry into Indigenous Health – ‘Health is Life’. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Division

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (2001) The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander coordinated care trials national evaluation report. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care

- Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care (2001) Better health care: studies in the successful delivery of primary health care services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2001) Expenditures on health services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 1998-99. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (2002) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce national strategic framework. Canberra: Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Research Agenda Working Group (2002) The NHMRC Road Map: a strategic framework for improving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health through research. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council

- Australian National Audit Office (2002) The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health program follow-up audit: Department of Health and Ageing. Canberra: Australian National Audit Office

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2002) Australia’s health 2002: the eighth biennial report of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- Office of Hearing Services, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (2002) Report on Commonwealth funded hearing services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: strategies for future action. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2003) The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2003. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Bureau of Statistics

- National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council (2003) National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: framework for action by governments. Canberra: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Council

- Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth Service Provision (2003) Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2003: overview. Canberra: Productivity Commission

- Social Health Reference Group (2003) Consultation paper for the development of the National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2004-2009 [draft]. Canberra: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005) Expenditures on health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, 2001-02. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- Steering Committee for the Review of Commonwealth Service Provision (2005) Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2005: report. Canberra: Productivity Commission

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2005) The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2005. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Social Health Reference Group (2004) Social and emotional well being framework: a national strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and social and emotional well being 2004-2009. Canberra: Australian Government

- Department of Health and Ageing (2005) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander sexual health and blood borne virus strategy 2005-2008: implementation plan. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing (Australia)

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner (2005) Social justice report 2005. Sydney: Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2006) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Australia, 2004-05. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics

- Department of Health and Ageing (2005) National strategic framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health 2003-2013: Australian Government implementation plan 2003-2008. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing

- Oxfam Australia (2007) Close the gap: solutions to the Indigenous health crisis facing Australia. Fitzroy, Vic.: Oxfam Australia

- Northern Territory Board of Inquiry into the Protection of Aboriginal Children from Sexual Abuse (2007) Ampe akelyernemane meke mekarle: little children are sacred. Darwin: Northern Territory Government

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (2006) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health performance framework 2006 report. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner (2007) Social justice report 2006. Sydney: Human Rights & Equal Opportunity Commission

- Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (2007) National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2003-2013: Australian Government implementation plan 2007-2013. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner (2008) Social justice report 2007. Sydney: Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Welfare Unit, Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (2008) Progress of the Northern Territory Emergency Response Child Health Check initiative: health conditions and referrals. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner (2010) Social justice report 2009. Canberra: Australian Human Rights Commission

- National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (2010) Aboriginal Health Workers formally acknowledged. Retrieved 2010 from http://www.naccho.org.au/Files/Documents/10-01-29%20Aboriginal%20Health%20Workers%20formally%20acknowledged%20Media%20Release.pdf

- Snowdon W (2010) New national coordinator to tackle Indigenous smoking. Retrieved 2010 from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/8049291939AEE69BCA2576CD00772DD1/$File/ws012.pdf

- Australian Government (2010) Closing the gap – Prime Minister’s report 2010. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia

- Close the Gap Steering Committee for Indigenous Health Equality (2010) Shadow report on the Australian Government’s progress towards closing the gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Canberra: Australian Human Rights Commission

- National Indigenous Health Equality Council (2010) National target setting instrument: evidence based best practice guide. Canberra: National Indigenous Health Equality Council

- National Indigenous Health Equality Council (2010) Child mortality target: analysis and recommendations. Canberra: National Indigenous Health Equality Council

- Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision (2010) Report on government services 2010: Indigenous compendium. Canberra: Productivity Commission

- Arabena K (2010) Vetting, vehicles and vision: the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples [Charles Perkins AO Annual Memorial Oration]. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2123/6765

- Fredericks B, Adams K, Angus S, Australian Women’s Health Network Talking Circle (2010) National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s health strategy. Melbourne, Vic: Australian Women’s Health Network

- Department of Families Housing Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2010) Budget 2010-11: Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs portfolio. Canberra: Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

- Australian Department of Health and Ageing (2010) National male health policy: building on the strengths of Australian males. Canberra: Australian Department of Health and Ageing

- Australian Department of Health and Ageing (2010) Third national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander blood borne viruses and sexually transmissible infections strategy 2010 – 2013. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing, Australia

- Department of Families Housing Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (2010) Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) redesign. Retrieved 2012 from http://www.fahcsia.gov.au/sa/indigenous/progserv/ctgnt/ctg_nter_redesign/Pages/default.aspx

- Snowdon W (2010) New peak body to support more Indigenous physiotherapists, dieticians, occupational therapists and optometrists. Retrieved 2010 from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/E760EC5038B456A7CA25775B0023B94D/$File/ws067.pdf

- Wilson L (2010) Ken Wyatt welcomed to parliament in traditional ceremony. Retrieved 2010 from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/ken-wyatt-welcomed-to-parliament-in-traditional-ceremony/story-fn59niix-1225930724882

- Gillard J (2010) Recognising Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the constitution. Retrieved 2010 from http://www.pm.gov.au/press-office/joint-media-release

- Snowdon W (2010) National workforce launched to tackle Indigenous smoking and improve health. Retrieved 2010 from http://www.health.gov.au/internet/ministers/publishing.nsf/Content/2CEE17F5C503949CCA2577F2008355CE/$File/ws082.pdf

- Gardiner-Garden J (1997) The origin of commonwealth involvement in Indigenous affairs and the 1967 referendum. Background Paper 11 1996-97. Retrieved from http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/BP/1996-97/97bp11.htm

Endnotes

i Prior to the referendum, the Constitution, as adopted in 1901, had made only two references to Indigenous people, both of which were exclusionary in nature. The first was in Section 51 where it was stipulated that ‘The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to: . (xxvi) The people of any race, other than the Aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws’. The second was in Section 127 which provided that ‘In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, Aboriginal natives shall not be counted’ [93].

ii The Program Effectiveness Review noted the debate between NAIHO, which was quoted as arguing for a plan to more than double the number of AMSs in order to replace the States grants programs, and the States who continued to defend their role in Indigenous health and their claim to the States grants. The report also recommended that, rather than the then system in which responsibility was shared between the Commonwealth Department of Health and the DAA, Indigenous health funds be transferred to the Department of Health [8].

iii Since 1973, when the Aboriginal Health Branch was established in the Commonwealth Department of Health, the administrative arrangements at Commonwealth level had become increasingly complex with the Departments of Health and Aboriginal Affairs having overlapping responsibilities for Indigenous health. A number of reports, including the 1980 Program Effectiveness Review , had recommended consolidation within one Commonwealth agency.

ivThe Development Group had estimated that the cost of addressing essential services and community infrastructure requirements alone would require $2.5 billion over 10 years, so it is likely that full implementation of the Strategy would have required around $3 billion over that time period.